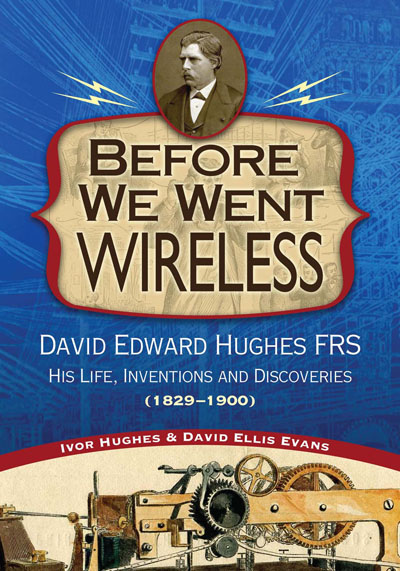

Before We Went Wireless: David Edward Hughes FRS, His Life, Inventions and Discoveries

By Ivor Hughes and David Elis Evans

This book is the first biography of the brilliant inventor and practical experimenter, David Edward Hughes. A contemporary of Edison and Bell, Hughes made major contributions in telegraphy, telephony, metal detection, audiology and wireless. His printing telegraph, adopted in America and Europe, made him a fortune, that he freely gave away to benefit society. Hughes sent and received wireless signals in 1879 using a portable wireless receiver coupled with a telephone receiver, some sixteen years before Marconi carried out his wireless tests.

The book is the fruit of over ten years of research in libraries, archives, and museums, as well as access to all of Hughes’s private papers and visits to places where Hughes lived and worked in the UK, US, and Europe, this is the definitive account of a great Victorian and highly decorated scientist whose inventions laid the foundations of the Communications Age.

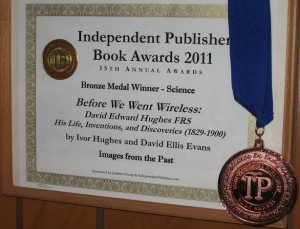

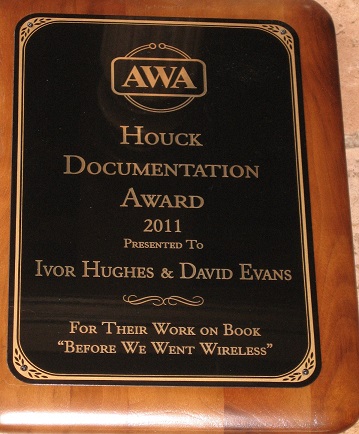

This book has received excellent reviews from the Smithsonian Institution, Science Museum in London and the prestigious Royal Society in the UK, the IEEE, BVWS and the A.S. Popov Central Museum of Communications St. Petersburg along with numerous literary critics. It has won the Independent Publishers Book Award (2011) for science and the AWA Houck award for the documentation of an important scientist.

You can watch the book trailer and the history of this project on YouTube here.

US Customers:

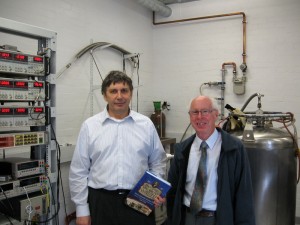

Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov were awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics for 2010 for their discovery of the two dimensional material Graphine. Andre Geim was also awarded the Hughes medal by the Royal Society in 2010. He is shown here receiving a copy of the D. E. Hughes Biography from the author to accompany the medal. For more information on the Royal Society, the Hughes medal, and its recipients go to the links page.

If you are interested in, purchasing the book or reading some of the reviews see the publisher Images from the Past

400 pages; 7″x10″

ISBN 978-1-884592-53-9 Paperback, $35.00

ISBN 978-18-84592-54-6 Hardcover, $49.50

Before We Went Wireless:

David Edward Hughes FRS His Life, Inventions, and Discoveries (1829-1900)

The book may also be purchased through your local book shop or from Amazon.com

UK Customers:

The book is available from the Welsh Books Council at Gwales

ISBN: 9781884592539 (1884592538) or through your local book shop.

Endorsements and Reviews

“Before We Went Wirelessis the stylish new biography of inventor David Edward Hughes, and it chuffs along like a great Victorian

locomotive…. Hughes not only invented the 19th century’s most commercially successful telegraph, in a stunning revelation authors Hughes and Evans detail beyond a doubt his discovery of wireless in 1880 nearly two decades before Marconi’s work arrives on the scene! How this happens and just why Hughes is moved to suppress his own invention makes for one of the great reads of technological history.”

Independent Publisher Book Awards, Bronze Metal in the Science Category, awarded in 2011 to Ivor Hughes and David Evans for their work on "Before We Went Wireless"

— Morgan Wesson, Writer, Journalist and Filmmaker whose credits include Alexander Graham Bell, and Empire of the Air with Ken Burns.

“We are indebted to the authors for, finally, an authoritative biography of this significant British-American musician-turned-inventor. Family papers (including a personal notebook) add valuable insights into his thinking processes and the role that music played in his work, as do separate detailed descriptions of his innovative printing telegraph, microphone and relay, among other devices…. This work is a valuable addition to the literature on nineteenth-century invention.” — Bernard Finn, Curator Emeritus of the Electrical Collections, Smithsonian Institution

“It is always with great pleasure that we hear of a new piece of scholarship on one of the perhaps lesser known names in our canon. Hughes sought to improve all of our lives and I sincerely hope that you enjoy reading about this great man.”

— Sir Peter Williams CBE FRS, Vice President and Treasurer of the Royal Society

“This deeply researched biography of David Hughes provides a much needed account of this important but neglected nineteenth-century electrical experimenter and inventor. The authors provide a lively narrative that follows his transatlantic adventures while offering fascinating and important insights into his life and work.”

— Paul Israel, Director and General Editor, Thomas A. Edison Papers, Rutgers University

“Considered obscure today, David Edward Hughes formed scientific connections with the Victorian era’s famous experimenters and theorists of electricity Thomas Edison, Lord Kelvin, and Alexander Graham Bell. This first biography rectifies an omission in the historiography of the technology in which Hughes was contemporaneously famous and successful, telegraphy. The authors’ access to Hughes’ papers and keen interest in the telegraph demonstrate where Hughes fit in. Unlikely enough, he was a child musical star in his Welsh family’s harp-playing act, which was popular enough to deposit Hughes in America. There a problem with the newfangled telegraph absorbed him; to wit, its tedious reliance on Morse code. His solution, a machine ancestral to the teletype, earned him a fortune and the leisure to tinker as he pleased (the microphone was a subsequent creation). Providing much detailed information, including even wiring diagrams, about Hughes’ devices, along with incidents of his generous personality and philanthropic life, the authors vitally contribute to technological history–and to the intriguing speculation that Hughes discovered radio waves before Heinrich Hertz.” –Gilbert Taylor, Booklist

“The title Before We Went Wireless is apropos for a book which chronicles the discoveries of Professor David Edward Hughes, FRS,* most of which were related to telegraphy and telephony by wire which predated Hertz’s discovery of electromagnetic radiation in 1888. However, from my viewpoint, the most important and interesting part of this book is Chapter 9 in which author Ivor Hughes (no relation to David Hughes) skillfully relates how Professor Hughes became the first ever to transmit and receive electromagnetic signals though the ether over distances approaching 500 yards in 1879—predating Hertz’s discovery of electromagnetic waves by nine years!

The author ably describes how Hughes’s work in telephony by wire led to his discovery of wireless communication, and also how Hughes was dissuaded from presenting his discovery to a meeting of the Royal Society of London in 1880 by Sir George Stokes. Had he presented his work to the Royal Society as he originally planned, the unit of radio frequency would undoubtedly now be “hughes” rather than “hertz.” Hughes’s decision not to publish his work represents the greatest missed opportunity in the history of electricity and magnetism.

The book begins with several chapters describing David Hughes’s roots in North Wales, his birth circa 1829, and his concert tours as a child prodigy playing the harp—first in the UK and later the US. His family

2011 AWA Houck Documentation Award, Presented to Ivor Hughes and David Edwards for their work on "Before We Went Wireless"

settled in Virginia where Hughes’s interest in science and experimentation emerged during his teens. While on a family trip through Mississippi in his late teens he was first exposed to the telegraph, then a new invention sweeping the country. He immediately saw the shortcoming of the Morse register or sounder which required the deciphering of code, and conceived of a revolutionary new type of printing telegraph instrument capable of transmitting letters of the alphabet by pushing on keys marked with letters, much like a typewriter, while simultaneously receiving and printing letters to form words, thus obviating the need for the operator to decipher code.

The next few chapters consist of a riveting account of how Hughes developed his concept into a working prototype and then struggled to have his new machine adopted in the US, only to be edged out by competing systems. In this endeavor, he encountered corporate intrigue, entrenched interests, feuding cable companies, infringers, greed and betrayal by associates. Learning from his experience in the US, David Hughes journeyed to Europe where he successfully introduced his system, first in France and then in many other countries, making it the international standard on the continent, if not in the UK. As a result, he achieved both fame and fortune as a respected inventor and experimenter, even though he was never formally trained as a scientist or theoretician.

Chapters seven and eight describe how Hughes discovered the microphone in 1878. His earliest devices consisted of loose contacts formed by crossed French nails, then metal filings, and finally carbon granules. Variations of these devices would become the detectors he used to receive electromagnetic radiation the following year. The publication of Hughes’s work on microphones resulted in an imbroglio with Thomas Edison who accused Hughes of stealing his discovery in the popular press of both the US and UK. In the end, Hughes was vindicated and there was no doubt, at least in Europe, about who had invented the carbon microphone, a version of which was almost universally adopted as the transmitter of choice for telephones. His further researches into reducing noise on telephone lines using another one of his discoveries, the induction balance, ultimately led him to his last and greatest discovery—the wireless transmission and reception of signals though the ether.

This book was clearly written with attention to detail, relying almost wholly on original sources which are cited in the extensive Notes section at the end of the book. While researching this book, Ivor Hughes travelled far and wide—for example, walking the dusty red earth lanes of Buckingham, Virginia where a century before David Hughes farmed and played music with his family as a youth. Ivor also walked Great Portland Street in London imagining David Hughes walking a century before with his first-of-a-kind wireless receiver listening to emissions from the spark-gap transmitter in his home laboratory. While in London, Ivor visited the Science Museum of London where he examined and photographed many of the artifacts that David Hughes used in his experiments, a number of which are beautifully reproduced in the book. He also reviewed many of Hughes’s notebooks containing detailed of his experiments, excerpts of which are sprinkled about the book.

The book ends by pointing out that David Edward Hughes never received the acknowledgements that were well deserved for his great accomplishments, an omission that this book is intended to redress. For those interested in the technical details of how Hughes’s telegraph keyboard machines worked, the three appendices following the twelve chapters of text will be a welcome supplement. This is one fine book—a “must-read” for anyone who wants to know how wireless transmission and reception of a series of dots (each evocative of the letter “e”) was first achieved, documented, and disclosed to prominent members of the Royal Society of London in 1879.”

*Fellow of the Royal Society